Putting our capability for improvement, resourcefulness, and creativity to use takes managing ourselves in a way that marshals that capability. If people act before having a target condition, they will tend to produce a variety of ideas and opinions about where to go and what to do. At each juncture they often end up shifting direction or simply selecting the path of least resistance.

Success depends on your challenge.

—Shinichi Sasaki, former TME President and CEO

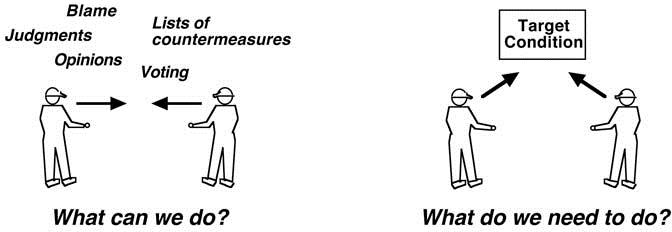

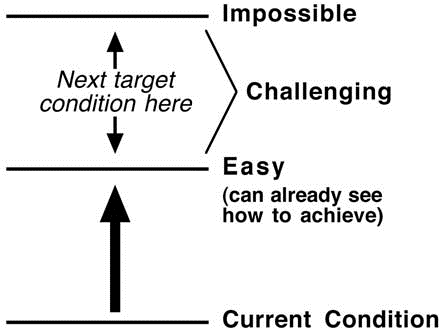

In contrast, a target condition—that is, a target pattern—creates a challenge that depersonalizes a situation (not your idea versus my idea about what we could do) and brings people’s efforts into alignment. The diagram in Figure 5-16 based on an insightful sketch by my colleague Bernd Mittelhuber, depicts this well.

Of course, it is not enough to simply set a challenging target condition and hope people will find a way to achieve it. Toyota’s improvement kata requires more than just that, and in the next chapter we will look at Toyota’s routine for how to move toward a target condition.

Figure 5-16. What a difference a target condition makes

Target Condition | Target

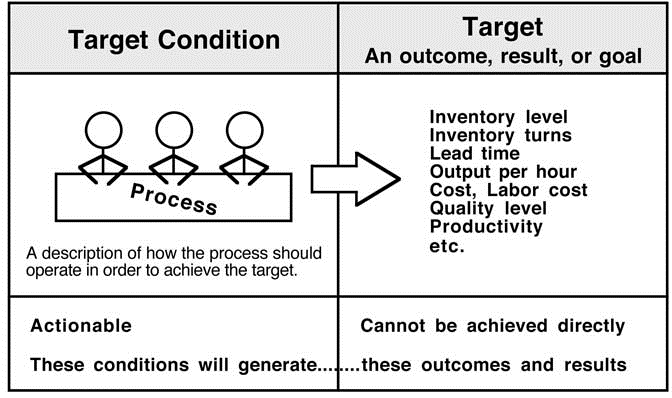

It is important to recognize the difference between a target and a target condition. A target is an outcome, and a target condition is a description of a process operating in a way—in a pattern—required to achieve the desired outcome (Figure 5-17). It may take some practice before this distinction becomes instinctively clear to you.

Unfortunately, when they are speaking English, Toyota people from Japan still often use the word target when they mean a target condition. This has led to misinterpretations by westerners who are accustomed to managing by setting quantitative outcome targets and focusing less on process details. When a Toyota person asks, “What is the target?” we naturally assume they are referring to a quantitative outcome metric. In actuality, a target condition as defined here is a good description of what Toyota people often mean when they say target.

Figure 5-17. Difference between a target condition and a target

The danger in not being clear about this distinction is that there are many different ways to achieve target outcome numbers, many of which have little to do with actually improving how processes are operating. Having numerical outcome targets is important, but even more important are the means by which we achieve those targets. This is where the improvement kata, including target conditions, comes into play.

For example, a quantitative cost reduction target by itself is not descriptive enough to be actionable by people in the organization. The overall goal may be to improve cost competitiveness, but having that alone will tend to make people simply cut inventory and people.

Inventory-reduction targets are also very common, and when utilized without associated process target conditions, cause a lot of problems. For instance, I have a nice award on my office wall that was given to me for increasing inventory. The plant manager at this particular factory had decreed a target of no more than one day of finished goods inventory, and people complied with this by reducing inventory. The result was a tremendous increase in expensive expedited shipping, because one day of inventory was too low for the current lot-size performance of the assembly processes. What I did was point out that the process, not the inventory, should be the focus of our attention.

I once ran into this while touring a Detroit factory with a group that included a mostly Japanese speaking former Toyota executive. At one point on the tour the Toyota person pointed and said, “More inventory here.” We chuckled and said, “Oh, your English is a little difficult to understand, but we know Toyota’s system and of course you mean less inventory here.” To which the former executive exclaimed, “No, no, no! More inventory here! This process is not yet capable of supporting such a low inventory level.”

It is easy to say “reduce inventory” and much harder to understand the appropriate and reasonably challenging next target condition for the processes causing that inventory. The inventory around and in a process is an outcome, and there are reasons it is there. We need to dig into the related processes themselves, set the next process target condition, and then tackle the obstacles that arise on the way to achieving that target condition. Then we will learn what it is that requires us to have so much inventory,

The Psychology of Challenge

An interesting question that is still debated is whether Toyota’s approach for continuous, incremental improvement would be appropriate for crisis and innovation situations, since in such situations we need to be more aggressive and fast in our efforts to improve. Interestingly, Toyota’s improvement kata—including the use of target conditions—resembles how we tend to manage and behave in crisis situations. At such times, it’s even more important to focus hard and resourcefully on what you need to do to achieve a challenging condition within the time, budget, and other constraints. You work in rapid cycles, adjust based on what you are learning along the way (see Chapter 6), and concentrate only on what you need to do. To some degree, Toyota is using its improvement kata to make a way of managing and working that we normally reserve for crisis situations an everyday way of working.

For example, the following may be difficult for many of us to accept and adopt, but it is one key to effectively utilizing our improvement capability: only work on what you need to work on. As people make suggestions for what to do, a reasonable question to ask is: “Do we expect this particular action to help us move toward the current target condition at this process?” If the action does not relate to a target condition, then it may be a good idea to stop spending time and resources on that action for now.

You may be thinking that, yes, some have proposed that we should create a crisis, but that’s not what I mean. It is easy to create a crisis situation and hope people will then work appropriately. That, by itself, is

still too much on the periphery and is not enough. What I mean is teaching people across the organization a behavior routine, a way to proceed, that mirrors good crisis behavior—behavior that aligns people and functions in accordance with the organization’s philosophy and vision. Then if you want to create a crisis, okay, because people will have an effective means for reacting to and proceeding through it. I can illustrate this with an experiment I have conducted many times. At a factory in Germany I took a group of engineers and managers to a shop-floor assembly process, equipped them with pencil, paper, clipboard, and stopwatches, and gave them, in writing, the following assignment:

Please observe this process.

- Do not conduct interviews, but observe for

- Make a written report on a flip chart answering the following question:

What do you propose for improvement?

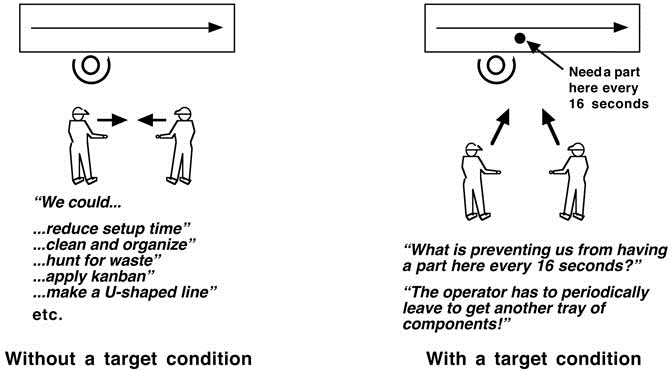

In this case, I had the participants work in pairs and asked each pair to observe a particular segment of the assembly process. One team focused on a particular line segment with one operator and generated the following broad brush list of proposals, which was not very useful. Their list was similar to what most of the other participants produced:

- Reduce setup time

- Clean up and organize the area

- Hunt for waste

- Several suggestions regarding workstation layout

- Apply kanban

- Make a U-shaped line so the operators are not isolated

After this first round of the experiment we went back and carefully analyzed the assembly process and defined a target condition that describes how the process should be operating. (In Appendix 2, I show you a process analysis procedure.) Armed with that process target condition, the teams were given exactly the same assignment and sent to observe the same line segments as before. The results are diagrammed in Figure 5-18.

In this second round of the experiment, the team that focused on the one-operator line segment made completely different and considerably more useful observations. Part of the process target condition was a planned cycle time of 16 seconds, which is to say that the line should be producing a part every 16 seconds. This team watched its line segment and timed for several successive cycles how often a part moved past a specific point. The cycle times they observed fluctuated widely; this line segment was not producing a part every 16 seconds. Then the team asked itself the following question:

“What is preventing us from having a part come by this point every 16 seconds?”

In trying to answer that question, the team observed that the operator had to periodically walk away from the line to get new trays of parts. Of course, this had an impact on the stability of the line cycle time. Can you see the entirely different nature of this team’s observations and thoughts before and after a process target condition was defined?

Another example, this one from several years ago. At a factory in Michigan that makes file cabinets, product development was once designing a new line of cabinets that were to be produced in an already existing file cabinet value stream. The production value stream would have to be reconfigured somewhat, and some capacity added, to accommodate the new products.

Figure 5-18. What a difference a target condition makes

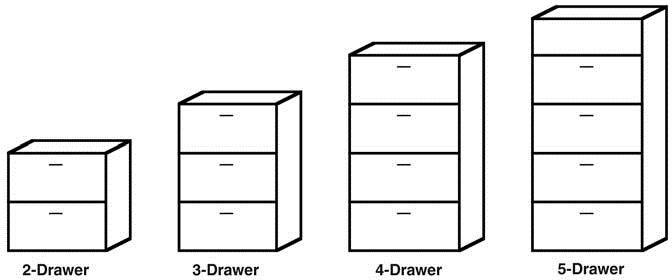

Figure 5-19. The four file cabinet sizes

File cabinets produced in this value stream came in four sizes, as shown in Figure 5-19.

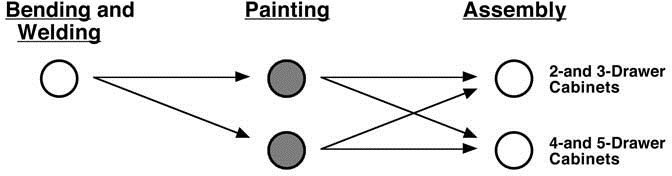

The three main processes for producing all files cabinets were: bending and welding sheet steel®painting®assembly. The current production flow is shown in Figure 5-20.

There was one bending/welding process, consisting of expensive, automated equipment. This process was, in particular, where additional capacity would be needed. Then there were two chain-conveyor paint lines, which already had sufficient capacity to handle the additional new cabinets. These paint lines and their conveyor systems were so monumental that no change was currently feasible here, which is why they are shaded in the diagram. Finally, there were two assembly lines: one for the smaller twoand three-drawer file cabinets, and one for the larger fourand five-drawer cabinets. The arrows show the material flow.

Figure 5-20. Current production flow

The debate among the engineers about how to configure the value stream had gone on for several weeks. There was still no consensus, but it was time to specify and order any necessary equipment. At this point I was asked to spend a week working with the team.

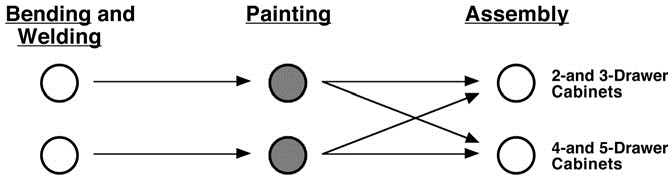

The production design team consisted of about 10 people, and during my first day with them our discussion went in circles. Someone would make a suggestion, such as having two bending/welding lines so there could be more dedicated flows, as in Figure 5-21.

The group would go in this direction for a while, until someone made the counterargument that a second bending/welding line would be too expensive for the budget.

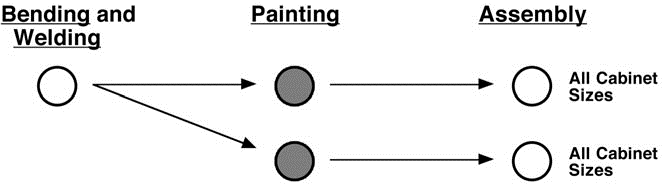

Then we would switch to another suggestion, such as altering the two assembly lines so each one could assemble all four cabinet sizes (Figure 5-22). This would be an advantage because sometimes big customers order predominantly the small or large sizes, which overwhelms one assembly line while the other sits idle.

Figure 5-21. First proposal: adding a second bend/weld line

Figure 5-22. Another proposal: universal assembly lines

This idea was pursued until someone pointed out that the operator work content and time was much higher for the larger cabinets than for the smaller cabinets, and that the line for small cabinets was elevated for better assembly ergonomics. Small and large cabinets were just too different from one another, and so again we switched to other ideas.

By the end of the first day we were no further along, and I sat in my hotel room thinking about what to do. As mentioned in Chapter 2, many group discussions and efforts go exactly this way. Whoever is most persuasive sets the tone and direction, until someone else has a convincing counterargument. In the worst cases, a voting technique is employed to give an artificial feeling that we know what to do.

Tuesday morning we began with a different approach. I asked the group what would be better, two bending/welding lines or one? Clearly two would be better because of the dedicated flows, but hands quickly went up in objection. “We have already been over that option several times. A second weld/bend line is too expensive.” We left the idea on the board, however. Then I asked if it would be better if both assembly lines could process all sizes of cabinets? “Yes, of course, but we’ve been over that option several times too. The small and large sizes are too different from one another.”

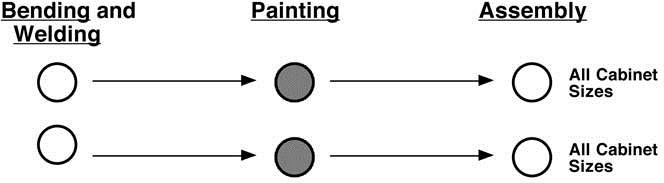

Then we drew the value stream shown in Figure 5-23 on the board.

Probably because I was an outsider, the group went along with me as I said, “Okay, no more discussion about where we want to go. This is our direction. Now let’s instead put all our effort and discussion into how we can achieve this condition within the allotted budget and time.” We had established a basic target condition.

Figure 5-23. A target condition

The change in the group dynamic was striking. We put one team of engineers on the challenge of adding a second bend/weld process within the budget constraints, and it was remarkable how creative and resourceful they were. Here are just a few excerpts from that team’s work during the rest of the week:

“We looked at an old unused weld line we have in the back of the plant, and there are several parts of that equipment we can reuse.”

“Maybe we can do without the expensive automatic transfer of steel sheets between the steps of the bending process.”

“We could utilize simple switches to enable or disable individual spot-weld tips depending on the size of the cabinet being welded, without using a numeric controller.”

The team assigned to modifying the two assembly lines so that each could handle all sizes was equally creative:

“How can we make a simple lift system for good ergonomics when a short cabinet comes down the line?”

“If we have a high-assembly-content cabinet coming down the line, let’s leave one pitch empty behind it so the operators have twice as long to work on it as on a small cabinet.”

Not all ideas could be implemented, and in the end the target condition we set for ourselves was not fully achieved this time, but the progress made was a great example of human capabilities … if we channel them.

Target Condition = Challenge

A target condition normally includes stretch aspects that go beyond current process capability. We want to get there, but we cannot yet see how. An interesting perspective on this was provided by Toshio Horikiri,

the CEO of Toyota Engineering Company Ltd., in a presentation he made at the Production Systems conference in Munich on May 27, 2008. Mr. Horikiri linked the degree of learning, fulfillment, and motivation to the level of challenge posed by a target condition. He proposed that both “easy” target conditions—ones that from the start we can already see how to achieve—and “impossible” target conditions, do not provide us with much sense of motivation and fulfillment (Figure 5-24). It is when a target condition lies between these extremes and is achieved that an adrenalinelike feeling of breakthrough and accomplishment is generated (“We did it!”), which increases motivation and the desire to take on more challenges.

Figure 5-24. Target conditions as a challenging but achievable stretch

A simple example: An operator at a metal-forming press fabricates small parts, which will later be painted and then used at an assembly process. The press operator carefully stacks the formed parts into their storage container, which makes it easier for the paint line operators to pick them up one by one. But the stacking takes too much time, and a suggestion is made to reduce time by having the press operator just drop these unsensitive metal parts into the container.

Right from the start we can see how to achieve this suggestion, which means there is probably no real improvement in the work system. It is a reshuffling of already existing ways of doing things or a shift of waste from one area to another. On the other hand, if we set a process target condition that includes stacking the parts in x time—x being less than the current time—we cannot immediately see how to achieve that. And when we do achieve it, then a true, creative process improvement will have been made.

As you define a target condition, you should not yet know exactly how you will achieve it. This is normal, for otherwise you would only be in the implementation mode. Having to say, “I don’t know,” often means that you are on the right path. If you want true process improvement, there often needs to be some stretch.

With this in mind, do not utilize a cost/benefit analysis (ROI) to determine what a target condition should be. That is the error the Detroit automakers’ managerial system led them to make whenever they tried to decide whether to also produce smaller cars. First define the next target condition—a condition that you need or want—then work to achieve it within budget and other constraints. A target condition must be achieved within budget, of course, but it normally takes resourcefulness to achieve the challenge within that constraint.