The applause dies down as the next conference speaker approaches the podium. The presentation is going to be about Toyota, and in his first slide the speaker presents some impressive statistics that demonstrate Toyota’s superior performance. The audience is nodding appreciatively.

For about two decades now this scene has been repeated countless times. So many books, articles, presentations, seminars, and workshops have begun with statistics about Toyota just like these:

- Toyota has shown sales growth for over 40 years, at the same time that U.S automakers’ sales reached a plateau or decreased.

- Toyota’s profit exceeds that of other automakers.

- Toyota’s market capitalization has for years exceeded that of GM, Ford, and Chrysler; and in recent years exceeded that of all three combined.

- In sales rank, Toyota has become the world leader and risen to the number two position in the United States.

Of course, such statistics are interesting and useful in only one respect: they tell us that something different is happening at Toyota. The question then becomes: What is it?

How have we been doing at answering that second question? Not so well, it seems. Books and articles about Toyota-style practices started appearing in the mid 1980s. Learning from such writings, manufacturers have certainly made many improvements in quality and productivity. There is no question that our factories are better than they were 20 years ago.

But after 15 to 20 years of trying to copy Toyota, we are unable to find any company outside of the Toyota group of companies that has been able to keep adapting and improving its quality and cost competitiveness as systematically, as effectively, and as continuously as Toyota. That is an interesting statistic too, and it represents a consensus among both Toyota insiders and Toyota observers.

Looking back, we naturally put Toyota’s visible tools in focus first. That is where we started—the “door” through which we entered the Toyota topic. It was a step in the learning process (which will also, of course, continue after this book). Since then I went back to the research lab—several factories—to experiment further, and present what I learned in this web.

The visible elements, tools, techniques, and even the principles of Toyota’s production system have been benchmarked and described many times in great detail. But just copying these visible elements does not seem to work. Why? What is missing? Let’s go into it.

We Have Been Trying to Copy the Wrong Things

What we have been doing is observing Toyota’s current visible practices, classifying them into lists of elements and principles and then trying to adopt them. This is reverse engineering—taking an object apart to see how it works in order to replicate it—and it is not working so well. Here are three reasons.

1. Critical Aspects of Toyota Are Not Visible

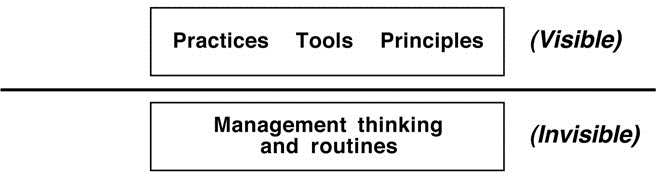

Toyota’s tools and techniques, the things you see, are built upon invisible routines of thinking and acting , particularly in management, that differ significantly from those found in most companies.

We have been trying to add Toyota Production System practices and principles on top of our existing management thinking and practice without adjusting that approach.

Toyota’s techniques will not work properly, will not generate continuous improvement and adaptation, without Toyota’s underlying logic, which lies beyond our view.

Toyota’s visible tools and techniques are built upon invisible management thinking and routines

Interestingly, Toyota people themselves have had difficulty articulating and explaining to us their unique thinking and routines. In hindsight this seems to be because these are the customary, pervasive way of operating there, and many Toyota people—who are traditionally promoted from within—have few points of comparison.

For example, if I ask you what you did today, you would tell me many things, but you would probably not mention “breathing.” As a consequence, we cannot interview people at Toyota and expect to gain, from that alone, the deeper understanding we seek.

2. Reverse Engineering Does Not Make an Organization Adaptive and Continuously Improving

Toyota opens its factory doors to us again and again, but I imagine Toyota’s leaders may also be shaking their heads and thinking, “Sure, come have a look. But why are you so interested in the solutions we develop for our specific problems? Why do you never study how we go about developing those solutions?”

Since the future lies beyond what we can see, the solutions we employ today may not continue to be effective. The competitive advantage of an organization lies not so much in the solutions themselves—whether lean techniques, today’s profitable product, or any other—but in the ability of the organization to understand conditions and create fitting, smart solutions.

Focusing on solutions does not make an organization adaptive. For example, several years ago a friend of mine visited a Toyota factory in Japan and observed that parts were presented to production-line operators in “flow racks.” Wherever possible the different part configurations for different vehicle types were all in the flow racks.

This way an operator could simply pick the appropriate part to fit the particular vehicle passing down the assembly line in front of him or her, which allows mixed-model assembly without the necessity of changing parts in the racks. Many of us have been copying this idea for several years now.

When my friend recently returned to the same factory, he found that many of the flow racks along that Toyota assembly line were gone and had been replaced with a different approach.

Many of the parts for a vehicle are now put into a “kit” that travels along with the vehicle as it moves down the assembly line. When the vehicle is in an operator’s workstation, the operator only sees those parts, and she always reaches to the same position to get the part.

My friend was a little upset and asked his Toyota hosts, “So tell me, what is the right approach? Which is better, flow racks or kitting?” The Toyota hosts did not understand his question, and their response was, “When you were in our factory a few years ago we produced four different models on this assembly line.

Today we produce eight different models on the same line, and keeping all those different part variations in the flow racks was no longer workable. Besides, we try to keep moving closer to a one-by-one flow. Whenever you visit us, you are simply looking at a solution we developed for a particular situation at a particular point in time.”

As we conducted benchmarking studies and tried to explain the reasons for the manufacturing performance gap between Toyota and other automobile companies, we saw at Toyota the now familiar “lean” techniques such as kanban, cellular manufacturing, short changeovers, andon lights, and so on.

Many concluded—and I initially did too—that these new production techniques and the fact that Western industry was still relying on old techniques were the primary reasons for Toyota’s superior performance.

However, inferring that there has been a technological inflection point is a kind of “benchmarking trap,” which arises because benchmarking studies are done at a point in time. Our benchmarking did not scrutinize Toyota’s admittedly less visible inner workings, nor the long and gradual slope of its productivity improvement over the prior decades. As a result, those studies did not establish cause and effect.

The key point was not the new production techniques themselves, but rather that Toyota changes over time, that it develops new production techniques while many other manufacturers do not. As Michael Cusumano showed in his 1985 book, The Japanese Automobile Industry, Toyota’s assembly plant productivity had already begun to inch ahead of U.S. vehicle assembly plant productivity as far back as the early 1960s! And it kept growing.

A deeper look inside Toyota did not take place until Steven Spear conducted research at Toyota for his Harvard Business School doctoral dissertation, which was published in 1999. It describes how Toyota’s superior results spring more from routines of continuous improvement via experimentation than from the tools and practices that benchmarkers had seen.

Spear pointed out that many of those tools and practices are, in fact, countermeasures developed out of Toyota’s continuous improvement routines, which was one of the impulses for the research that led to this book.

3. Trying to Reverse Engineer Puts Us in an Implementing Mode

Implementing is a word we often use in a positive sense, but—believe it or not—having an implementation orientation actually impedes our organization’s progress and the development of people’s capabilities. We will not be successful in the Toyota style until we adopt more of a do-it-yourself problem-solving mode. Let me use an example to explain what I mean by an implementation versus a problemsolving mode.

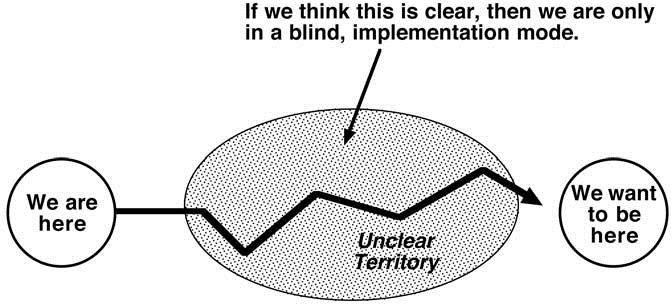

During a three-day workshop at a factory in Germany, we spent the first two days learning about what Toyota is doing. On the third day we then turned our attention to the subject of how do we wish to proceed? During that part of the workshop, a participant raised her hand and spoke up. “During the last two days you painted a clear picture of what Toyota is doing.

However, now that we are trying to figure out what we want to do, the way ahead is unclear. I am very dissatisfied with this.”

My response was, “That is exactly how it is supposed to be.” But this answer did not make the workshop participant happy, which led me to drawing the diagram in Figure.

The implementation mode is unrealistic

There are perhaps only three things we can and need to know with certainty: where we are, where we want to be, and by what means we should maneuver the unclear territory between here and there. And the rest is supposed to be somewhat unclear, because we cannot see into the future!

The way from where we are to where we want to be next is a gray zone full of unforeseeable obstacles, problems, and issues that we can only discover along the way. The best we can do is to know the approach, the means, we can utilize for dealing with the unclear path to a new desired condition, not what the content and steps of our actions—the solutions—will be.

That is what I mean in this book when I say continuous improvement and adaptation: the ability to move toward a new desired state through an unclear and unpredictable territory by being sensitive to and responding to actual conditions on the ground.

Like the workshop participant in Germany, humans have a tendency to want certainty, and even to artificially create it, based on beliefs, when there is none. This is a point where we often get into trouble.

If we believe the way ahead is set and clear, then we tend to blindly carry out a preconceived implementation plan rather than being sensitive to, learning from, and dealing adequately with what arises along the way. As a result, we do not reach the desired destination at all, despite our best intentions.

If someone claims certainty about the steps that will be implemented to reach a desired destination, that should be a red flag to us. Uncertainty is normal—the path cannot be accurately predicted—and so how we deal with that is of paramount importance, and where we can derive our certainty and confidence.

I can give you a preview of the rest of this book by pointing out that true certainty and confidence do not lie in preconceived implementation steps or solutions, which may or may not work as intended, but in understanding the logic and method for how to proceed through unclear territory.

How do we get through that territory? By what means can we go beyond what we can see? What is management’s role in this?

What Is the Situation?

As most of us know, the following describes the environment in which many of our organizations find themselves.

- Although they may seem steady state, conditions both outside and inside the organization are always changing. The process of evolution and change is always going on in your environment, whether you notice it or not. The shift may at times be so slow or subtle that your way of doing things does not show up as a problem until it is late. Try looking at it this way: if your working life was suddenly 100 years long instead of 35, would you still expect conditions to remain unchanged all that time?

- It is impossible for us to predict how those conditions will develop. Try as we might, humans do not have the capability to see the future.

- The future is fundamentally different than it appears through the prospectiscope. —Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness

- If you fall behind your competitors, it is generally not possible to catch up quickly or in a few leaps. If there was something we could do, or implement, to get caught up again quickly, then our competitors will be doing that too.

The implication is that if we want our organization to thrive for a long time, then how it interacts with conditions inside and outside the company is important. There is no “finish line” mentality. The objective is not to win, but to develop the capability of the organization to keep improving, adapting, and satisfying dynamic customer requirements. This capability for continuous, incremental evolution and improvement represents perhaps the best assurance of durable competitive advantage and company survival. Why?

Small, incremental steps let us learn along the way, make adjustments, and discover the path to where we want to be. Since we cannot see very far ahead, we cannot rely on up front planning alone. Improvement, adaptation, and even innovation result to a great extent from the accumulation of small steps; each lesson learned helps us recognize the next step and adds to our knowledge and capability.

Relying on technical innovation alone often provides only temporary competitive advantage. Technological innovations are important and offer competitive advantage, but they come infrequently and can often be copied by competitors. In many cases we cannot expect to enjoy more than a brief technological advantage over competitors.

Technological innovation is also arguably less the product of revolutionary breakthroughs by single individuals than the cumulative result of many incremental adaptations that have been pointed in a particular direction and conducted with special focus and energy.

Cost and quality competitiveness tend to result from accumulation of many small steps over time. Again, if one could simply implement some measures to achieve cost and quality competitiveness, then every company would do it. Cost and quality improvements are actually made in small steps and take considerable time to achieve and accumulate.

The results of continual cost reduction and quality improvement are therefore difficult to copy, and thus offer a special competitive advantage. It is highly advantageous for a company in a competitive environment to combine efforts at innovation with unending continuous improvement of cost and quality competitiveness, even in the case of mature products.

Relying on periodic improvements and innovations alone—only improving when we make a special effort or campaign—conceals a system that is static and vulnerable. Here is an interesting point to consider about your own organization: in many cases the normal operating condition of an organization—its nature—is not improving.

Many of us think of improvement as something that happens periodically, like a project or campaign: we make a special effort to improve or change when the need becomes urgent. But this is not how continuous improvement, adaptation, and sustained competitive advantage actually come about. Relying on periodic improvement or change efforts should be seen for what it is: only an occasional add-on to a system that by its nature tends to stand still.

The president of a well-known company once told me, “We are continuously improving, because in every one of our factories there is a kaizen workshop occurring every week.” When I asked how many processes there are in each of those factories he said, “Forty to fifty.” This means that each process gets focused improvement attention approximately once a year.

This is not bad, and Toyota utilizes kaizen workshops too, but it is not the same thing as continuous improvement. Many companies say, “We are continually improving,” but mean that every week some process somewhere in the company is being improved in some way. We should be clear:

Projects and workshops continuous improvement

Let’s agree on a definition of continuous improvement: it means that you are improving all processes every day. At Toyota the improvement process occurs in every process (activity) and at every level of the company every day. And this improvement continues even if the numbers have already been met. Of course, from day to day improvement may involve small steps.

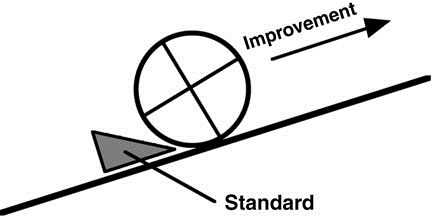

We cannot leave a process alone and expect high quality, low cost, and stability. A popular concept is that we can utilize standards to maintain a process condition (Figure).

Standards depicted as a wedge that prevent backsliding. It doesn’t work this way.

However, it is generally not possible simply to maintain a level of process performance. A process will tend to erode no matter what, even if a standard is defined, explained to everyone, and posted.

This is not because of poor discipline by workers (as many of us may believe), but due to interaction effects and entropy, which says than any organized process naturally tends to decline to a chaotic state if we leave it alone (I am indebted to Mr. Ralph Winkler for pointing out to me the second law of thermodynamics). Here is what happens.

In every factory, small problems naturally occur every day in each production process—the test machine requires a retest, there is some machine downtime, bad parts, a sticky fixture, and so on—and the operators must find ways to deal with these problems and still make the required production quantity. The operators only have time to quickly fix or work around the problems, not to dig into, understand, and eliminate causes.

Soon extra inventory buffers, work-arounds, and even extra people naturally creep into the process, which, although introduced with good intention, generates even more variables, fluctuation, and problems. In many factories management has grown accustomed to this situation, and it has become the accepted mode of operating. Yet we accuse the operators of a lack of discipline. In fact, the operators are doing their best and the problem lies in the system—for which management is responsible.

The point is that a process is either slipping back or being improved, and the best and perhaps only way to prevent slipping back is to keep trying to move forward, even if only in small steps. Furthermore, in competitive markets treading water would mean falling behind if competitors are improving. Just sustaining, if it were possible, would in that case still equal slipping.

Quality of a product does not necessarily mean high quality. It means continual improvement of the process, so that the consumer may depend on the uniformity of a product and purchase it at a low cost.

—W. Edwards Deming, 1980

Finding Our Way into the Future

By What Means Can Organizations Be Adaptive?

While nonhuman species are subject to natural selection—that is, natural selection acts upon them—humans and human organizations have at least the potential to adapt consciously. All organizations are probably to some degree adaptive, but their improvement and adaptation are typically only periodic and conducted by specialists.

In other words, such organizations are not by their nature adaptive. As a consequence, many organizations leave a considerable amount of inherent human potential untapped.

How do we achieve adaptiveness? What do we need to focus on?

Although we have tended to believe that production techniques like cellular manufacturing and kanban, or some special principles, are the source of Toyota’s competitive advantage, the most important factor that makes Toyota successful is the skill and actions of all the people in the organization. As I see it now, this is the primary differentiator between Toyota and other companies. It is an issue of human behavior.

So now we arrive at the subject of managing people.

Humans possess an astounding capability to learn, create, and solve problems. Toyota’s ability to continuously improve and adapt lies in the actions and reactions of the people in the firm, in their ability to effectively understand situations and develop smart solutions. Toyota considers the improvement capability of all the people in an organization the “strength” of a company.

From this perspective, then, it is better for an organization’s adaptiveness, competitiveness, and survival to have a large group of people systematically, methodically, making many small steps of improvement every day rather than a small group doing periodic big projects and events.

Toyota has long considered its ability to permanently resolve problems and then improve stable processes as one of the company’s competitive advantages.With an entire workforce charged with solving their workplace problems the power of the intellectual capital of the company is tremendous.

—Kathi Hanley, statement as a group leader at TMMK

How Can We Utilize People’s Capabilities?

Ideally we would utilize the human intellect of everyone in the organization to move it beyond forces of natural selection and make it consciously adaptive. However, our human instincts and judgment are highly variable, subjective, and even irrational. If you ask five people, “What do we need to do here?” you will get six different answers.

Furthermore, the environment is too dynamic, complex, and nonlinear for anyone to accurately predict more than just a short while ahead. How, then, can we utilize the capability of people for our organization’s improvement and evolution if we cannot rely on human judgment?

If an organization wants to thrive by continually improving and evolving, then it needs systematic procedures and routines—methods—that channel our human capabilities and achieve the potential. Such routines would guide and support everyone in the organization by giving them a specific pattern for how they should go about sensing, adapting, and improving.

Toyota has a method, or means, to do exactly that. At Toyota, improvement and adaptation are systematic and the method is a fundamental component of every task performed, not an add-on or a special initiative. Everyone at Toyota is taught to operate in this standard way, and it is applied to almost every situation. This goes well beyond just problem-solving techniques, to encompass a firm-specific behavior routine. Developing and maintaining this behavior in the organization, then, is what defines the task of management.

My definition of management:

The systematic pursuit of desired conditions by utilizing human capabilities in a concerted way.

Upon closer inspection, Toyota’s way, as it is sometimes called, is characterized less by its tools or principles than by sets of procedural sequences—thinking and behavior patterns—that when repeated over and over in daily work lead to the desired outcome. These patterns are the context within which Toyota’s tools and principles are developed and function. If there is one thing to look at in trying to understand and perhaps emulate Toyota’s success, then these behavior patterns and how they are taught may well be it.

Kata

In Japan such patterns or routines are called kata (noun). The word stems from basic forms of movement in martial arts, which are handed down from master to student over generations. Some common translations or definitions are:

- A way of doing something; a method or routine

- A pattern

- A standard form of movement

- A predefined, or choreographed, sequence of movements

- The customary procedure

- A training method or drill

Digging deeper, there is a further definition and translation for the word:

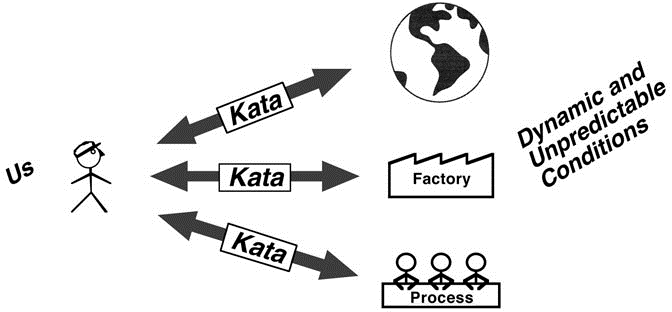

- A way of keeping two things in alignment or synchronization with one another

Eureka! This last definition is of particular interest with regard to the dynamic conditions that exist outside and inside a company (Figure). It suggests that although conditions are always changing in unpredictable ways, an organization can have a method, a kata, for dealing with that. This is an interesting prospect.

A kata is a means for keeping your thoughts and actions in sync with dynamic, unpredictable conditions

Such a method would connect the organization to current circumstances in the world, inside the organization, and in its work processes, and help it stay in sync—in harmony—with those circumstances.

A key concept underlying kata is that while we often cannot exercise much control over the realities around us, we can exercise control over—manage—how we deal with them.

Kata are different from production techniques in that they pertain specifically to the behavior of people and are much more universally applicable. The kata described in this book are not limited to manufacturing or even to business organizations.

Kata are also different from principles. The purpose of a principle is to help us make a choice, a decision, when we are confronted with options, like customer first, or pull, don’t push. However, a principle does not tell us how to do something; how to proceed, and what steps to take.

That is what a kata does. Principles are developed out of repeated action, and concerted repeated action is what a kata guides you into. Toyota’s kata are at a deeper level and precede principles.

What, then, might be some attributes of a behavior form, a kata, that is utilized for continuous improvement and adaptation?

The method would operate, in particular, at the process level. Whether in nature or in a human organization, improvement and adaptation seem to take place at the detail or process level. We can and need to think and plan on higher levels, like about eliminating hunger or developing a profitable small car, but the changes that ultimately lead to improvement or adaptation are often detail changes based on lessons learned in processes.

It is finally becoming apparent to historians that important changes in manufacturing often take place gradually as the result of many small improvements.

Historians of technology and industrial archeologists must look beyond the great inventors and the few revolutionary developments in manufacturing; they must look at the incremental innovations created year after year not only in the drafting room and the mind of the engineer but also on the shop floor and in “the heart of the machinist.” Maybe then we will begin to learn about the normal process of technological change

—Patrick M. Malone, Ph.D., Brown University

If the objective is to improve in every process every day, then the kata would be embedded in and made inseparable from the daily work in those processes. The kata would become how we work through our day.

Since humans do not possess the ability to predict what is coming, the method that generates improvement and adaptation

would be content neutral; that is, it would be applicable in any situation. The method, the procedure, is prescribed, but the content is not.

Since human judgment is not accurate or impartial, the method would, wherever possible, rely on facts rather than opinions or judgments. In other words it would be depersonalized.

The method for improvement would continue beyond the tenure of any one leader. Everyone in the organization would operate according to the method, regardless of who is in charge at the moment.

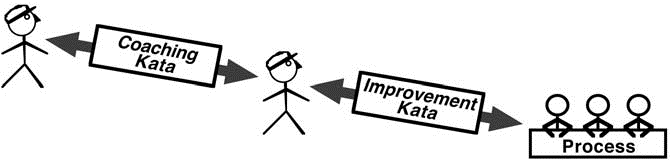

We will examine in detail what are perhaps Toyota’s two most fundamental kata (Figure). One I call the improvement kata (Part III), which is the repeating routine by which Toyota improves, adapts, and evolves. The improvement kata exactly fits the attributes spelled out above and provides a highly effective model for how people can work together; that is, how to manage an organization. The second I call the coaching kata (Part IV), which is the repeating routine by which Toyota leaders and managers teach the improvement kata to everyone in the organization.

Two fundamental Toyota kata

The Management Challenge

Based on what I have been learning, the challenge we face is not to turn the heads of executives and managers toward implementing new production or management techniques or adopting new principles, but to achieving systematic continuous evolution and improvement across the organization by developing repeatedly and consistently applied behavioral routines: kata.

Note that this challenge is significantly different than what we have been working on so far in our lean implementation efforts, and is primarily an issue of how we manage and lead people. Some adjustment in how we have been trying to adopt “lean manufacturing” will be necessary.

Before we go on I should mention that the idea of standardized behavioral routines often generates a prognosis that they will disable our creativity and limit our potential.

What if, however, we can be even more creative, competitive, smart, out-of-the-box, and successful precisely because we have a routine that does a better job of tapping and channeling our human capabilities? A difference lies in what we define as the routine.

Notably, Toyota’s improvement kata does not specify a content—it cannot—since that varies from time to time and situation to situation, but instead only the form that our thinking and behavior should take as we react to a situation.

Humans derive a lot of their sense of security and confidence— what psychologist Albert Bandura calls “self-efficacy,” from predictable routines: from doing things the same way again and again.

However, it’s not possible for the content of what we do to stay the same, and if we try to artificially maintain it, it causes problems, because we are then adjusting to reality far too late and in a jerky manner.

Any organization whose members can face unpredictable and uncertain situations (which are the norm) with confidence and effective action, because they have learned a behavioral routine for doing that, can enjoy a competitive advantage.

Toyota’s improvement kata is an excellent example of this second kind of routine. It tells us how to proceed, but not the content, and thus gives members of the organization an approach, a means, for handling an infinite variety of situations and being successful.

We may be standing before a different way of operating our organizations, which can take us toward nearly any achievement we might envision.

But to see that, we have to grasp the current situation: how we are managing our organizations today.