Origin and Effects of Our Current Management Approach

Much of our current managerial template comes out of the United States automobile industry of the 1920s, and a short, focused look back at the early history of its two giants, the Ford Motor Company and the General Motors Corporation, sheds light our current thinking.

The original thinking behind management by objectives (MBO), as outlined by Peter Drucker in his 1954 book The Practice of Management, is not too distant from how Toyota is managing. Drucker even mentions, in a short case example, how what he calls “some of the most effective managers I know” go beyond only deploying quantitative targets downward. He briefly describes how these managers engage in a two-way dialogue with the level below them in order to develop written plans for the activities that will be undertaken to reach the targets. In other words, paying attention to the means that are utilized to achieve the results.

It appears, however, that in subsequent actual business practice and education, MBO became something more like planning and control from above executed to a large degree by setting quantitative targets and assessing reports of metrics. Some call this “management by results.” Unfortunately, there are plenty of different ways to achieve a quantitative outcome target, many of which have nothing to do with making real process improvement and moving the pieces of an organization in a common direction.

So why did a watered-down version of MBO work so well for us for so long? Here are some possible reasons:

- In the period of limited international competition and continued growth, which ran until the 1970s, occasional improvement was good enough. In such market conditions it is possible to make a good profit even if there is considerable waste in the system and we are not continually

- In those market conditions, there were still some profitable choices available, and thus less need for nurturing products and situations into

- As the need for improvement and evolution became apparent in the midto late 1970s, it may have been possible to stay ahead for a while by simply cutting inventories and head count, which might have been bloated. Today, however, we might well be reaching the limits of improving by simply

- The competition was ramping up only slowly, which made it seem as if conditions were not changing all that

Interestingly, moving production to lower-cost countries in order to reduce cost—another form of cutting—does not change the underlying system or improve the production process. Some have called this “making waste cheaper,” because it does not actually change the underlying way of doing things.

What Are the Lessons from This History?

Lesson 1

Simply put, after the Model T era the basic attributes of factory flow in the West barely changed during the rest of the twentieth century, as a consequence of the management system. There were, of course, many technological developments since the end of the Model T days, but as Michael Cusumano, in his early 1980s Ph.D. research, and the famous late 1980s IMVP study, both asserted, from 1930 to the 1980s there was little further development in productivity and factory flow (inventory turns) in Western automobile factories. The basic production techniques stayed about the same.

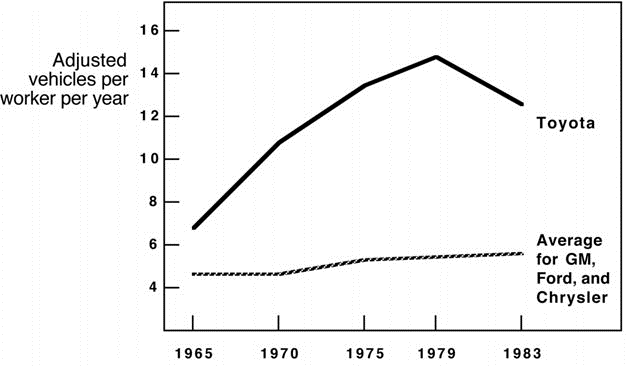

Toyota’s way of moving forward, in contrast, is very much one of adaptation and continuous improvement; of nurturing processes, products, and businesses into profitability by doing what is necessary to achieve target conditions (Figure 4-5).

Figure 4-5. Productivity trends,Toyota and the Detroit Big Three Source: Michael A. Cusumano, The Japanese Automobile Industry:Technology & Management at Nissan & Toyota (Cambridge, Massachasetts: The Harvard University Press, 1985).

Lesson 2

In the early 1950s the baton of continuous process improvement toward the ideal flow vision was picked up again, and this time by Toyota. In production, for example, Toyota decided to keep working step by step toward something like the early Ford Motor Company vision: a connected and synchronized flow with ever shorter lead time. In fact, both early Ford and Toyota have referred to the production ideal as “one long conveyor.”

Toyota recognized that a main source of low cost is not high machine utilization by itself, but rather when parts flow uninterrupted from one process to the next with little waste in between. For Toyota, striving toward this kind of a synchronized flow meant taking on the challenge of eliminating or reducing the time required to change over between the different items required by the customer.

Lesson 3

The most important lesson to derive from this chapter is that many of us are managing our companies with a logic that originated in the 1920s and 1930s, a logic that might not be appropriate to the situation in which your company finds itself today.

GM’s approach proved highly lucrative during the period of growth and oligopolistic isolation from global competition that extended until the 1970s. It became our model and accepted management practice, and is still taught in business schools today. That means, for many of us the way we currently manage our companies is built on logic that originated in the conditions faced by companies in the U.S. automobile industry during the late 1920s. The problem is not that the logic is old, but that it does not incorporate continuous improvement and adaptation. If our business philosophy and management approach do not include constant adaptiveness and improvement, then companies and their leaders can get stuck in patterns that grow less and less applicable in changing circumstances.

The solution is not to periodically change your management system or to reorganize, but to have a management system that can effectively handle whatever unforeseeable circumstances come your way. The fact that Toyota has maintained much of its same management thinking for the past 60 years is a testament to this. Several of us are curious to see how Toyota’s management system will maneuver and weather the next few decades.

Let us now take a look at that management system.

Notes

- Keep in mind as you go through this chapter that in retrospect all history is revisionist, and despite my best efforts to dig deep and be impartial, that undoubtedly holds true for this history as

- The elevation drawing is found in: Horace Lucien Arnold and Fay Leone Farote, Ford Methods and the Ford Shops (New York: The Engineering Magazine Company, 1915).

- Testimony of Edward Gray, Ford Tax Cases, 1927, page

- Alfred Sloan, Jr., My Years with General Motors (New York: McFadden-Bartell, 1965).

- Peter Drucker, The Practice of Management (New York: HarperBusiness, 1993). Originally published in 1954.