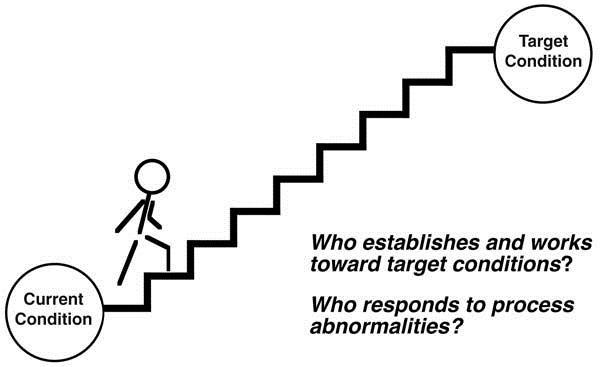

A question that has been debated for many years is: “Who should carry out process improvements?” (Figure 7-1). Here are three common but problematic answers to that question.

- The process operators? One of the widely held opinions about continuous improvement at Toyota is that it is primarily selfdirected, with teams of production operators autonomously making improvements in their own processes. Some typical comments along these lines are:

“The operators are closest to the process and are empowered.” “How can we get our line operators to solve problems?” “How can we make continuous improvement run by itself?”

Operator autonomy is a commonly held and unfortunate misconception about Toyota’s approach. It is not at all how operators and improvement are handled at Toyota. For one, it is unfair and ineffective to ask operators on their own to simultaneously make parts, struggle with problems, and improve the process, which is why Toyota calls autonomous operator-team concepts, “Disrespectful of people.”

Figure 7-1. Working toward a target condition

It is physically impossible for production operators to work fully loaded to the planned cycle time in a 1x1 production flow and simultaneously make process improvements. Furthermore, many operators are just beginning to develop their understanding of the improvement kata and their problem-solving skills. There are currently no autonomous, self-directed teams at Toyota.

This does not mean that we should not empower or engage process operators. In fact, teaching people the improvement kata by engaging them in it is critical to Toyota’s success. It only means that concepts like self-directed work teams are not such an effective way for an organization to empower and engage people.

- Leave it to chance? I have not heard anyone actually give this answer, but in many cases our comments and actions—comments like these—indicate this is exactly what is happening:

“Andon gives everyone in the plant information.” “This alerts everyone that there is a problem.” “Any person walking through the area can see …”

The number of andon-style warning-lamp systems that have been installed in our factories in the last 20 years, for example, is astonishing. Yet in many factories the red lamps are lighting up and no one is responding. The basic point here is that if we assume anyone (or everyone) is responsible, then no one is responsible.

- A special team? As we have already discussed, this will not work if we want improvement to occur at every process every At Toyota, factory staff includes no specific continuous improvement agents. The improvement kata is embedded into every work process, and everyone is taught to work along the lines of the improvement kata.

Who Does It?

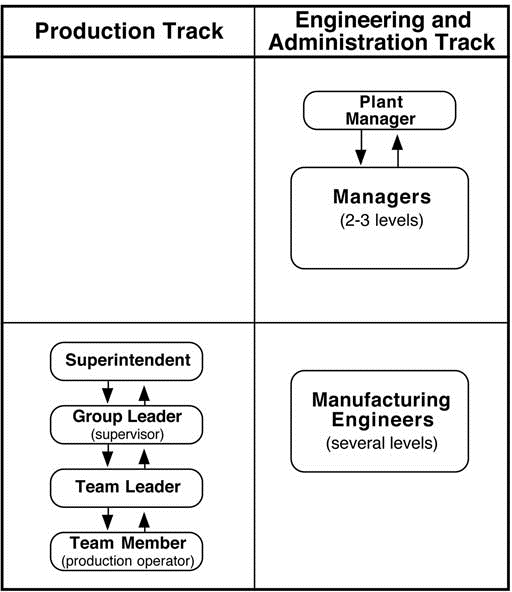

In schematic form, a typical Toyota factory’s line functions are organized as shown in Figure 7-2. There are, of course, additional support

Figure 7-2. Schematic of Toyota factory line organization

functions such as maintenance and production engineering that are not shown, but this diagram is detailed enough for our purposes.

In 2004, Professor Koichi Shimizu of Okayama University published a paper about continuous improvement of production processes in Toyota factories. In his paper, Shimizu classifies process improvement activity at Toyota in two categories:

- Improvement carried out by production operators themselves through quality circles, the suggestion system, and similar initiaShimizu calls this “voluntary improvement activity.”

- Improvement carried out by team leaders, production supervisory staff, and engineers as part of their job

There are some surprises in Shimizu’s paper (Figure 7-3). Specifically, his research suggests that only about 10 percent of realized improvement in productivity and cost at Toyota comes from the first category, whereas about 90 percent comes from the second. In addition, the main purpose of the first category—improvements carried out by production operators themselves—is not so much the improvement itself, but rather to train production operators in kaizen mind and ability, and to identify workers who are candidates for promotion to team

| Who | Impact | Purpose | |

| Production operators themselves through quality circles and suggestion system | Only 10% of realized

improvement comes from this |

Training of kaizen mind and ability

Identify workers to promote to team leader |

|

| Team leaders, | 90% of realized | Cost reduction | |

| production | improvement | via improvement | |

| supervisory staff, | comes from this | in productivity | |

| and engineers as | and quality | ||

| part of their job | |||

| function |

Figure 7-3. Who carries out process improvements at Toyota?

Source: Koichi Shimzu, “Reorienting Kaizen Activities at Toyota: Kaizen, Production Efficiency, and Humanization of Work,” Okayama Economic Review, vol. 36, no. 3, Dec. 2004, pp. 1-25.

leader. The purpose of the second category of improvement, on the other hand, is clearly cost reduction via diligent and constant improvement of productivity and quality.

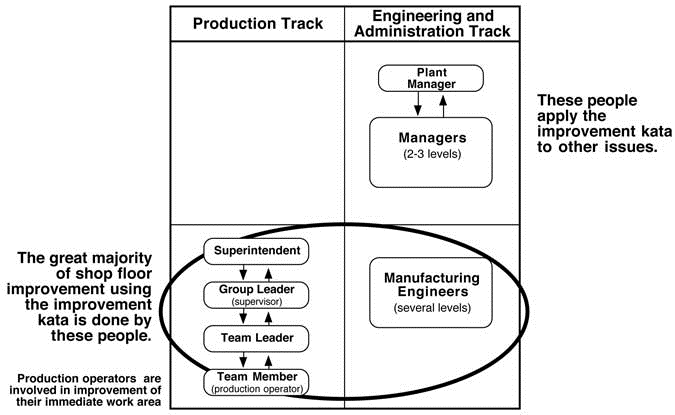

What I have been able to learn so far about who makes process improvements on Toyota shop floors fits with Shimizu’s findings. The great majority of shop floor improvement in a Toyota factory is generated by the functions circled in Figure 7-4. These team leaders, group leaders, superintendents, and various levels of manufacturing engineers are the primary people who apply, and coach application of, the improvement kata to production processes. This process improvement activity represents well over 50 percent of their work time, which is not surprising since at Toyota the improvement kata is actually a way of managing.

Toyota production operators, called “team members,” are of course also regularly involved in making process improvements, but these are usually improvements in the operators’ immediate work envelope, which are carried out in collaboration with, and under the guidance of, the team leader. It’s the responsibility of team leaders to encourage and get improvement suggestions from their team members, and, conversely, operator promotion to team leader is determined in part on how much improvement initiative and skill an operator demonstrates. Both operator and team leader, in other words, have incentive to work together on process improvement.

Figure 7-4. In the factory organization, process improvement activity is mostly here

Working with Target Conditions

In the case of a new process or product, management sets a target cost and a target date for production. The first process target condition (that is, work standard) is typically established by the process’s group leader and a production engineer. This is then given to the production team (the team leader and team members).

As the production stage begins, the production team and their group leader work to achieve that target condition, which can take several weeks. Once regular production stabilizes, then further target conditions, called “standards” or “targets,” are developed:

- Group leaders, team leaders, and team members focus on target conditions in their process, and on understanding and resolving daily production problems.

- Themes, targets, plans, and initiatives are announced by senior These are worked down into the organization via mentor/mentee dialogues (more on this in the next chapter), and are converted into process target conditions. The conversion of outcome targets into process target conditions generally begins at the “superintendent” level. Managers at this level ensure that target conditions, improvement efforts, and projects at individual processes follow improvement-kata thinking, fit together for a flowing value stream, match with the organization’s targets, and serve customer requirements.

Responding to Process Abnormalities

A common way of reacting to process abnormalities in our factories is to have production operators record them, so they can be compiled into summaries and Pareto charts. Sounds like a good idea, but it is not effective for improvement. I once listened to a plant manager proudly explaining a Pareto chart of problems and how the top problem was being

worked on. One of my colleagues said in response, “Oh, and the rest of those problems you are shipping to the customer?” which I thought was a pretty good insight.

The information provided by Pareto charts usually comes too late to be useful for process improvement efforts. By the time a problem has risen to the top of a Pareto chart, it has already caused a lot of damage and grown complicated, the root-cause trail is cold, and we become involved in analyzing postmortem data instead of understanding what is actually happening on the shop floor now. It is interesting to note how often the largest category in a Pareto chart is “other,” that is, an accumulation of smaller problems.

This does not mean that Pareto charts should be abolished, but that they should not be thought of as our first choice for becoming aware of and dealing with process problems.

Here are two aspects of how Toyota thinks about dealing with process problems:

- The response to process abnormalities should be Why?

- If we wait to go after the causes of a problem, the trail becomes cold and problem solving becomes more We lose the opportunity to learn.

- If left alone, small problems accumulate and grow into large and complicated

- Responding right away means we may still be able to adjust and achieve the day’s

- Telling people that quality is important but not responding to problems is saying one thing but doing

- Lean value streams are closely coupled, and a problem in one area can quickly lead to problems

- The response to process abnormalities should come from someone other than the production operators. Why?

An example helps here. Imagine a 1x1 flow assembly cell in one of our factories with an “autonomous” team of operators. In the cell, there is a status counter that displays two numbers. One number is the actual quantity produced, which increases each

time a finished item is scanned. The second number is the target quantity, which increases automatically as each takt time interval passes.

What happens in this process when one operator experiences a problem? The cell stops. What do the operators do? They try to fix the problem so they can resume production. Say it takes a few minutes to do that, during which time the target-quantity counter continues to advance. Now the problem is fixed and the cell is able to run again. What do the operators do? Naturally they resume production, probably as quickly as possible since the line is now a little behind according to the status counter. Yet the moment the problem occurred, while the trail is hot, is the best time to learn why it happened. Looking into it later will be fruitless.

Can you see the conflict in our thinking? Do we want the operators to make parts, or do we want them to go into problem investigation? They cannot do both simultaneously. Problems are normal, and if we set up autonomous processes, there is no way the operators can be successful. These kinds of autonomous production processes seem to reflect a flawed assumption that if everyone did what they were supposed to do, there would be no problems.

In order to be able to respond to process problems as they occur, production processes at Toyota-group companies are supported and monitored by a team leader. This team leader is the designated person to respond first and immediately to any process problem. Although team leaders respond to every abnormality, each response does not trigger problem-solving activity, which is usually initiated in response to repeating problems. The process’s work standard—the target condition—is owned by the team leader, who uses it to help spot abnormalities in the process. The team leader is not monitoring the process to police its failings, but to be acquainted with how it is working.

With team leaders at its processes, Toyota has—in comparison to many other factories—one official extra level of indirect staffing. This does not sound “lean,” but it is an enabler for process improvement because there is someone to respond as problems occur, and the root

cause trail is still hot. As mentioned earlier, you can expose problems only to the degree that you can handle them. With its team leader approach, Toyota can handle more problems and can thus learn and improve more.

Having a fast-response system in place then gives Toyota the ability to staff its production processes with no more than the correct number of operators, which in turn quickly reveals problems. This combination represents an improving system. Conversely, manufacturers with autonomous teams of operators generally need to have extra operators in their processes, which, as already mentioned, causes work-arounds, obscures problems, and leads to a static system.

Interestingly, at Toyota, having this improvement and response system—team leaders—does not equal having more people in total compared to other companies. On the contrary. There are two reasons for this:

- Because of the team leader’s presence, the process can be staffed with only the correct number of operators; no extra.

- Because there is an improvement and response system in place, beginning with the team leader, over time productivity is improved and even fewer operators are

We should be careful with overly simple, quick-benefit statements such as “cut indirect labor” or “flatten the organization chart,” because they can lead to suboptimization and a dangerously static system.

Notes

- The information under this heading comes from observations and interviews at Toyota facilities, and discussions with several former TMEMNA

- Manufacturing engineers at Toyota are responsible for improvement in shop floor operations. This is different from what the words “manufacturing engineer” mean to Toyota also has what it calls “production engineers,” who, like manufacturing engineers in our factories, are responsible for developing tools, processes, machines, and equipment.